Every picture tells a story— and these preschoolers in class at the East Boston YMCA tell an important tale about Massachusetts’ future.

They represent the African American and Latino/a children who now comprise 30 percent of the state’s population under the age of five. As they pass through the K–12 system, these children will, if recent trends hold, perform better on MCAS, graduate from high school in greater numbers, and enter college at higher rates than ever before.

There, the good news typically ends. Unless current rates of degree production at Massachusetts public colleges and universities improve markedly, too few of the preschoolers pictured here can be expected to earn a college degree, creating an unacceptable loss of brainpower in a state with a voracious need for new college graduates.

Fifty miles away at Mount Wachusett Community College’s Fitness & Wellness Center, another vision of the state’s future dances into view. Participants in the Silver Sneakers® fitness program glide across a gym floor in their Wednesday morning exercise class.

No one in this group has come to campus to study or earn a degree; the seniors are here to relax and enjoy themselves after long years in the workforce. In the next decade their ranks will swell, as an estimated 660,000 college-educated workers across Massachusetts retire.

Combined with a seven percent decline in the state’s population of high school graduates, these trends impacting the state’s youngest and senior citizens offer extraordinary challenges for a public higher education system that now educates more than half of all undergraduates— and more than 70 percent of Latino/a and African American students seeking college degrees.

“When we look at demographic changes occurring in Massachusetts, we can see that the current metrics on college completion are certainly concerning, especially in under-represented communities like the ones we serve,” said Valerie Roberson, president of Roxbury Community College. “At RCC and other campuses that serve our neediest students, we’re working to address the barriers that typically prevent completion.”

Although Massachusetts prides itself on being the state with the most adult degree-holders—51.5 percent of adults ages 25–54—research conducted by the Department of Higher Education shows that demographic changes are taking a toll. By 2022, the overall rate at which young residents earn college degrees will pivot from growth to decline unless the public higher education system can find ways to raise college completion rates for all students, including those from underserved populations and communities.

Already, the demand for qualified graduates with degrees in high-need fields such as computer science and nursing has begun to outstrip supply. “Massachusetts’ population projections and educational attainment rates portend critical shortfalls in the supply of labor needed to sustain the state’s leading industries,” declares the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) Massachusetts Combined State Plan, the state’s official workforce plan released in spring 2016. The warning echoes the finding of a 2014 report from MassINC and the UMass Donahue Institute, which predicted that, for the first time since data was collected, “Massachusetts will end a decade with fewer prime working age college-educated residents than it (started) with.”

In last year’s Degrees of Urgency report, the Department of Higher Education projected that by 2025, the state’s community colleges, state universities and campuses of the University of Massachusetts would fall short of producing their share of the state’s much-needed new college degrees by a minimum of 55,000 to 65,000. This year, a more detailed analysis shows that 80 percent of those lost degrees will be at the baccalaureate level or higher.

The specific nature of the Massachusetts economy, with its rapid job growth in health care and science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields, helps explain the state’s outsized need for more highly educated graduates. An analysis of online job data by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce shows that Massachusetts leads the nation with 63 percent of its online job postings requiring a four-year degree or higher.

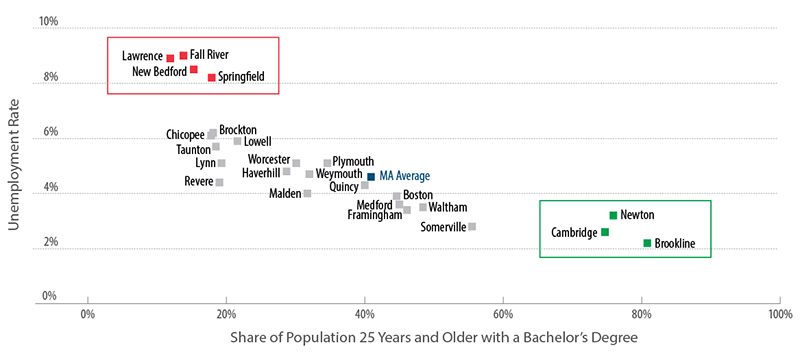

The size and depth of the Commonwealth’s talent pool has direct bearing on the strength of its economy. In February 2016, the New England Economic Partnership forecast that, by 2018, Massachusetts’ economic growth rate would drop by half, from 3% to 1.5%, precisely because the state will not produce enough college-educated workers to fill jobs in high-demand industries. Perhaps not surprisingly, Massachusetts communities with the lowest percentages of college-educated workers—Springfield, New Bedford, Lawrence, Fall River—have the state’s highest unemployment rates.

“Massachusetts is in the midst of its most robust economic expansion of the century, but to date the benefits of this economic growth have yet to be experienced in any meaningful way by our regions outside of Greater Boston,” observes Michael Goodman, professor and executive director of the Public Policy Center (PPC) at UMass Dartmouth and co-editor of MassBenchmarks, the journal of the Massachusetts economy published by the UMass Donahue Institute in cooperation with the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. “In particular, our urban communities and the young and the poorly educated are growing more and more disconnected from our economy and society, and we are paying an increasingly high price for this divergence of destinies. Our aging population and slow-growing labor force are expected to curb job growth significantly in coming years. This makes closing the achievement gap and improving access to affordable and high-quality higher education an essential economic and social imperative.”

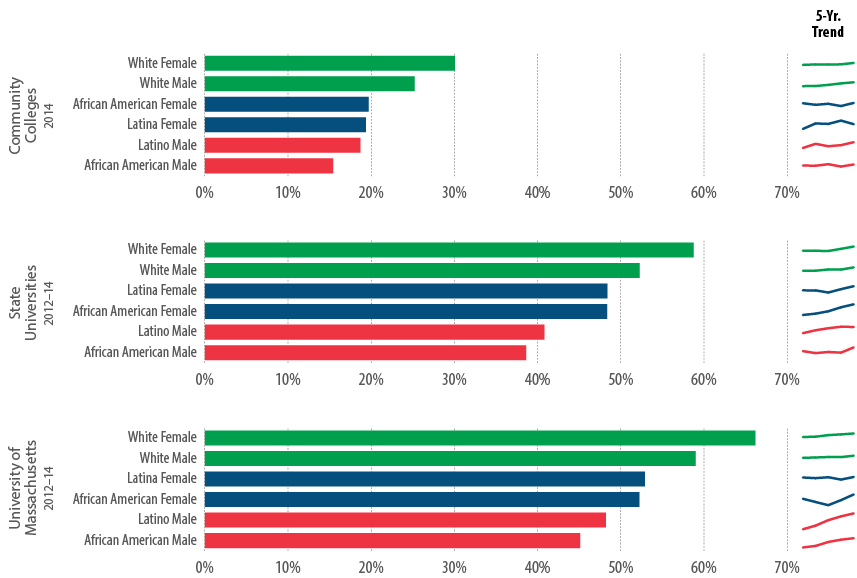

For graduates holding college credentials, employment prospects are strong. But for students who never earn their college diplomas, the best-paying jobs and most fulfilling opportunities remain well beyond reach. In particular, college graduation rates for students of color remain troublingly low, with little system-level change over the years. In Massachusetts, 79 percent of Latino/a undergraduates and 72 percent of African American undergraduates attend a public college or university; yet six years after beginning their studies, less than one third of these students earn college credentials.

“These gaps on their own are a non-story,” says Michael Collins, associate vice president for postsecondary state policy at Jobs for the Future. “They’ve been there since Brown versus the Board of Education; we see them in every state, every year. The real story is whether there is actual intention at the state level to close them. Who are the outliers, the deviants who are having success in closing gaps? That’s where we need to look, to see progress.”

In the all-important tech sector, another degree gap is visible along gender lines, creating a further drag on hiring within the industry. Only one in five students earning a degree in computer science or information technology from a public college or university is female.5 (Learn more in the Demand for Diversity story)

Thanks largely to a boomlet of millenials, Massachusetts public colleges and universities were able to expand baccalaureate degree production by a robust annual average of 4.6 percent from 2011 to 2015. But the number of students who actually finish college—while improving at many individual campuses—is not growing fast enough to offset the overall degree shortage facing the Commonwealth. Meanwhile, low college completion rates for students of color and low-income students continue to exacerbate degree shortages, limiting both human and economic potential.

“If we cannot continue to provide the skilled workers that our growing employers demand, they will look elsewhere and the state economy and its working families will be the poorer for it,” Goodman emphasizes. “In short, we can no longer afford to leave any of our people or communities behind. Extending more and better educational opportunities to our workers and their families is a no-brainer in an economic environment where we rely so critically on our highly skilled workforce and our world-class innovation economy.”